When Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin looked out in awe across the lunar landscape, he offered a two-word, visceral, description: “magnificent desolation”. As I flew over southwestern Afghanistan on a cloudless day, I understood his sentiment perfectly. Fifty-thousand square miles of red sand and dirt were laid out before me in a single, breathtakingly beautiful, image.

Peering down through my aircraft’s drift-sight, I noticed something out of place in the vast nothingness far below. It was a long, well-defined, dust trail stretching on for miles. Following it from its wide tail to its pinpoint source, I struggled to see who, or what, was generating it. After a few passes and with a little help, I was locked on and had it clearly identified.

To my astonishment, I was looking at a large, heavily loaded, ox-drawn wagon with a family sitting atop. The questions cascaded across my mind: who were these people; how did they get there; where were they going in all this “magnificent desolation”?

Then the next layer: what motivated their seemingly impossible journey; what skills must they possess to strike across oblivion; what kind of courage and determination must it take?

As I pondered these and many other questions, I marveled at the irony of it all. A 21st Century man, peering down from the edge of space at a man whose civilization and lifestyle had changed little since the 8th Century. I thought of what we might have in common, knowing I would always be as much a stranger in his world as he was in mine.

After the mission that night, I tried to sleep but couldn’t. My ears were plugged from breathing 100% O2 for hours on end, my muscles ached, and I was still feeling the residual of the amphetamines I’d taken hours before, despite the sleeping pills. Finally, fed-up with hours of continuous crocodile turns in my uncomfortable mattress, I got out of bed and headed to the recreation trailer.

Finding one of the few empty computers with limited internet access, I logged-on to send an email home. I tried to explain to my wife what I saw and the impact it was having. I tried, as best I could, to describe the beauty of a sunrise over the Hindu-Kush mountains and how, when seeing the first thin red sliver of dawn, hours before anyone on the ground below could, it felt like a promise fulfilled—I had made it through another long, dark, lonely night.

After hitting “send” on another stream-of-consciousness missive, a plastic mail-bucket caught my wandering eye. A quick sift through its contents revealed a treasure-trove of letters from school children with messages of support and encouragement. I was moved.

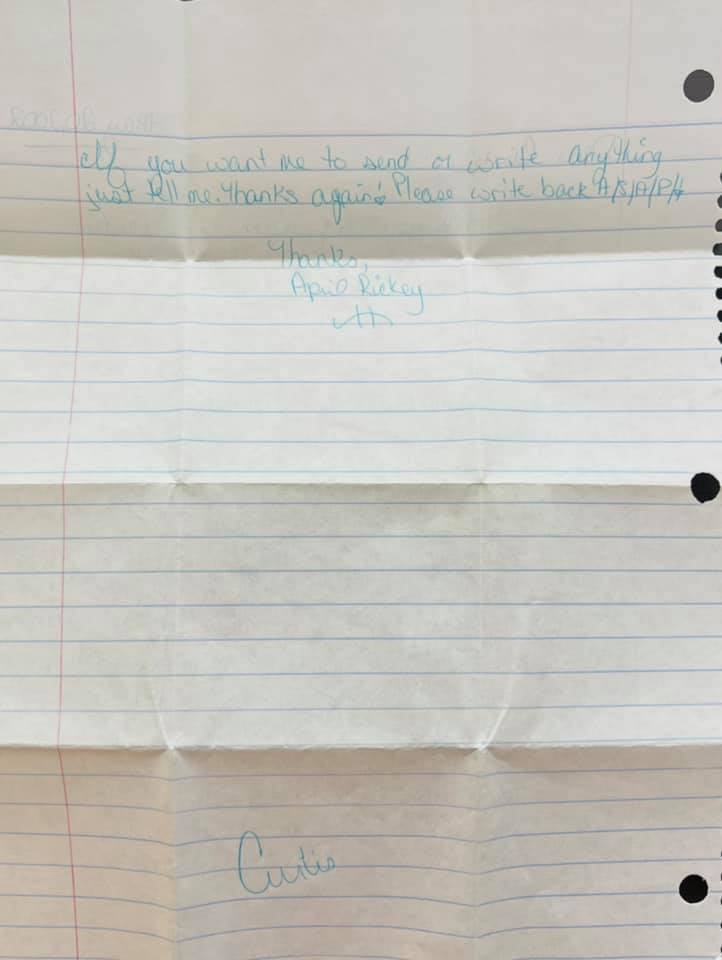

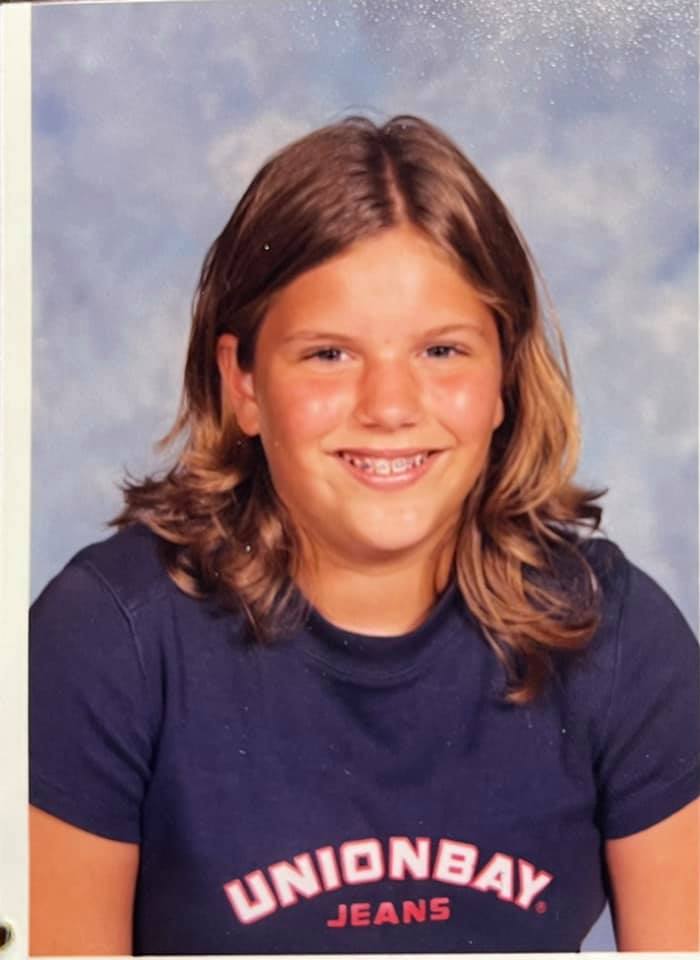

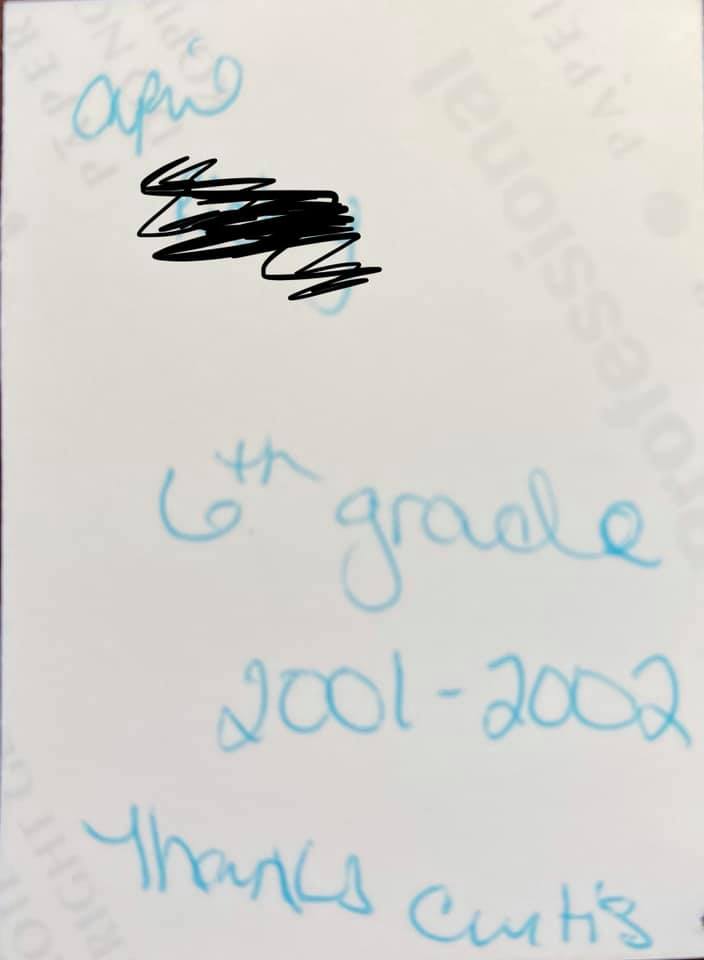

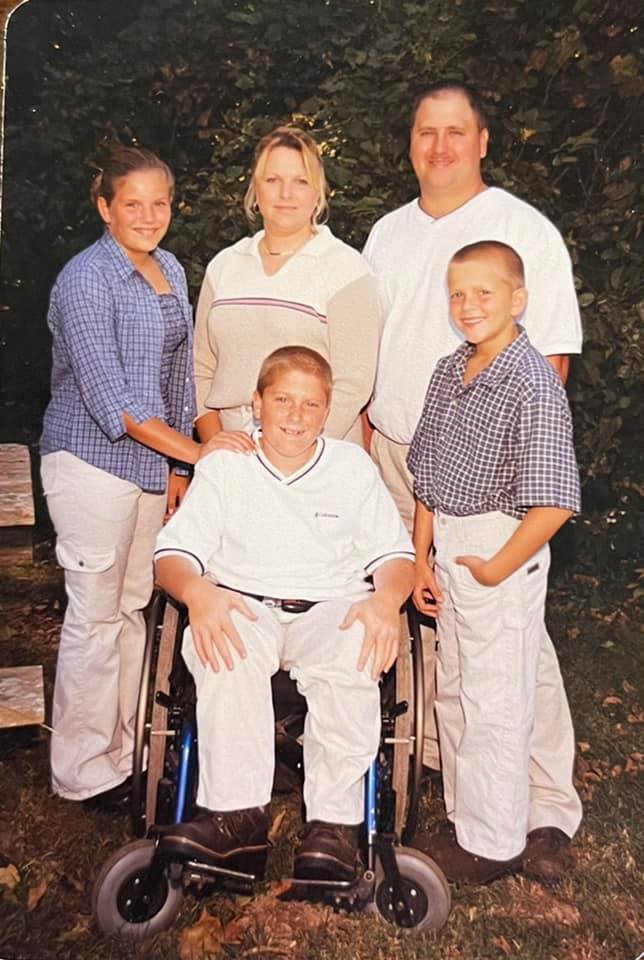

One letter, in particular, grabbed my attention. It was from a sixth-grader in Farmington, Illinois, population: 2600. She talked about her family, her brother with cerebral palsy, and her hard-working parents. Maybe it was her honesty, innocence or eloquence that drew me to her letter; maybe it was her life America’s heartland, from where so many of my ancestors hailed; or maybe, her letter had caused me to reflect on why I was so far from home—why we were all there, instead of our homes.

I put pen to paper to thank her for her kindness, attempt to explain why we were there, and offer inspiration for her life ahead. Taking my Mission Patch out of my bag, I dropped it in the envelope and placed it in the mail.

As I headed back to my hooch for elusive rest, I put away the nagging reality that I had more questions than answers and more doubts than certainties.